Painting the Snake

I am not interested in the discourse that swirls around the question of whether or not remakes should exist. They remain, they persist, and they are a part of culture, whether we like it or not. Most importantly, they are not beyond critical reproach.

I am not interested in the discourse that swirls around the question of whether or not remakes should exist. They remain, they persist, and they are a part of culture, whether we like it or not. Most importantly, they are not beyond critical reproach.

I am not opposed to the ideas of remakes in themselves. I do not hold art as a sacred, immutable practice, one that does not invite copy, retracing and reimagining through the reiteration of known narratives or mechanics. It is possible to reinvent existing games in ways that produce interesting insights or mechanical engagement.

When I reviewed the Silent Hill 2 remake for Superjump, I posited two claims: that there’s no perfect formula for a “successful” remake and that the best remakes often invoke the memory of the original. Metal Gear Solid Delta: Snake Eater has me contradicting my point. It is a game that promises remembrance, the faithful retreading of paths already walked, but it irredeemably loses its identity when its jungles are slathered in glossy veneer.

Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater has style, and style will always overcome realism because while graphics are temporary, style is timeless. The video game industry has proven, time and time again, that the remakes it produces act as hazy and faded memories rather than true reimaginings of beloved games of yesteryear. At their worst, remakes are soulless husks devoid of charm. Few actually possess the artistic intent to reenvision old games in meaningful or innovative ways. We are always marching toward the next big thing, the next approximation of the human skin but not the soul. The Snake Eater remake suffers because it is a paradoxical game: simultaneously the same as it was in 2004, yet struggling to find an interesting and engrossing visual identity of its own.

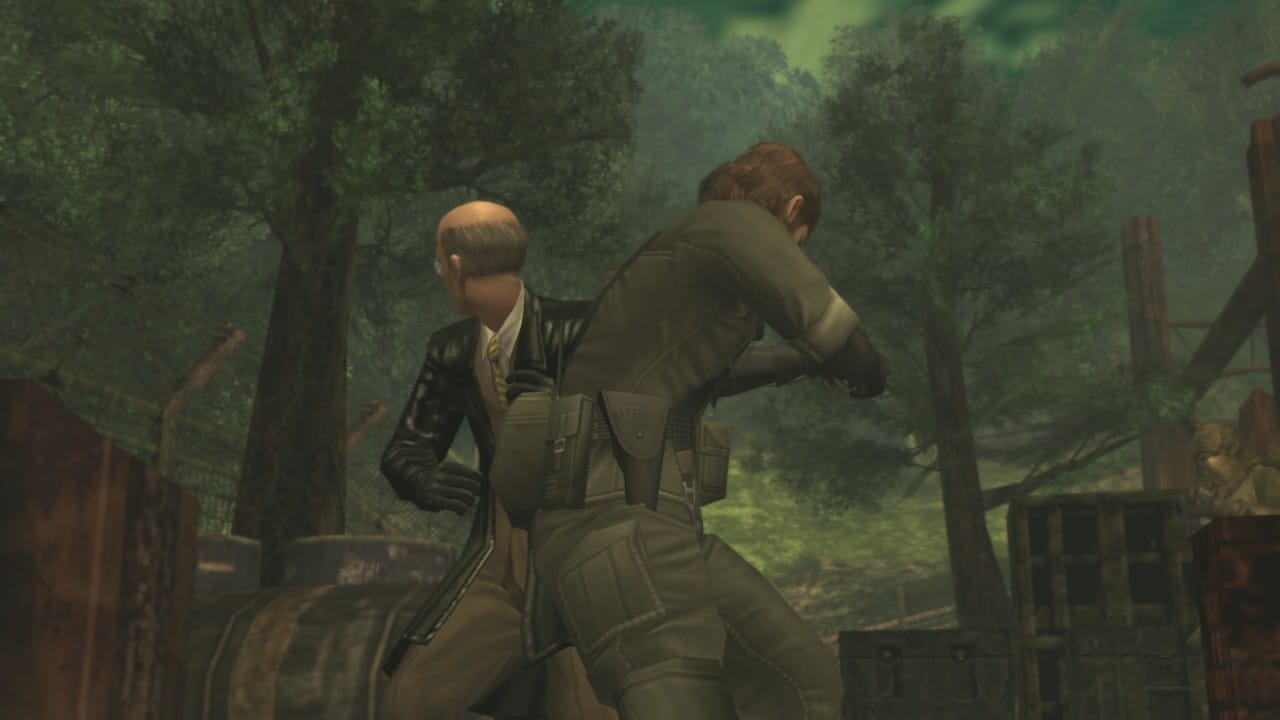

Metal Gear Solid Delta has no blood. It is devoid of life. Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater looked (and still looks) like nothing else, but it has been revived into a game that resembles every other one out there — a product of an industry-wide hyperfixation on graphical realism. Gone are the angular and geometric character designs born from hardware limitations, replaced by amalgamations of flesh shellacked with a shiny coat that peels at the corners. Everything looks like it’s made of plastic — artificial and inorganic.

When Naked Snake sinks his teeth into a serpent, the creature’s fleshy viscera oozes and glistening blood drips from its limp body. When he is gifted his customized M1911 pistol, it gleams in sharp detail. The addition of these fine details, which only high-fidelity graphical realism can offer, might enhance the effectiveness of a game’s minutiae. But, the remake of the stealth-action classic showcases these details in sterile scenes, losing the pathos the game usually submerges the player in.

A faithful one-to-one recreation, in which the only reimagination is graphical opulence, the remake is unable to recreate the experience of the original. It retains the same voice acting, the same gameplay functions, and the same wacky cutscenes full of physics-defying stunts. But the new and “improved” graphics add nothing. They take away from the experience. They’ve injected light into the places where darkness should prevail.

Even the gameplay innovations detract from the experience. Call it an archaic control scheme if you will, but the clunky design of the original Snake Eater makes it so every action you take has weight and a sense of commitment and consequence. When you replace those controls with a modern third person shooter scheme, you ruin the tempo of combat. I can move and shoot at the same time, turning the remake into a more by-the-numbers video game. No longer do I have to confront each member of the Cobra unit with tactics and guile: I can shoot the Pain while I am swimming, I can more easily aim at the Fear as he darts from tree branch to tree branch, the sniper duel with the End is devoid of tension and stillness, and the claustrophobic corridors of the Fury’s boss fight are easier to maneuver.

There’s a synergy to the various elements of the original Snake Eater, as if the art style is dancing alongside the gameplay mechanics. It feels this way because the developers had to consider it deeply — they had to grind and toil and unpack how the complexity of play could be explored. They had to design the original game as a whole, whereas the remake just needs to redesign and revisit it. But they also had to think about how the game looked, while operating within the hardware limitations of the time. So they made it look painterly.

It is this synchronous nature, in which all the elements of the game are in conversation with another, that is lost on the sacrificial altar of remakes. This is why I am not obsessed with the idea that remakes should just be faithful revisitations — if it’s the same game but with added visual fidelity, give me the original with its intended art style, or, scratch it, give me something entirely new.

The biggest loss is that the original aesthetic informs the game’s themes better than photorealism.

Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater is magic. There was no other way to conceive of it in my 11-year-old mind. The complex mechanical interactivity I could engage with in this virtual world through freedom of play was nothing less than a revelation. I know Snake Eater is magic: it bisects a massive jungle into puddle-sized playgrounds that manage to be as deep as oceans.

The game drew me in at a young age, not necessarily because of its mechanical complexity — at 11, I was a bit too happy to resort to fisticuffs and shootouts. In the folly of youth, I lacked the patience for sneaking and engaging with the game’s complicated bits and bobs. No, what attracted me to the original Snake Eater was that it always looked like a painting in motion.

My camouflage bleeds into the wet earth. I grab an enemy from behind and my knife becomes a paintbrush.

It is colorful, even while operating with a limited palette — greens and browns bloom onscreen. The enemy wears camouflaged auscam jackets, and you paint them red with their blood. The rain fuzzes the same way it does when I’ve had a few beers, and kuwabara kuwabara, the lightning flashes. It feels handcrafted in a way that Delta does not, despite the fact that I know in my heart and mind that the remake had plenty of passion and devotion behind it, and that even the original used cutting-edge graphical technology for its time.

Snake Eater has style. It has always had style. It is obsessed with detail, hyper-realism without photorealism, and it is all the better for it, because it will live forever and so will its message. Paintings persist: with preservation and care, they can live on when the animal meat starts to rot.

There is soul in the PlayStation 2 version of Snake Eater that is sorely lacking in the remake.

I cry every time I revisit it, when the newly-honored Big Boss salutes his mentor at the graveyard. When I was too young to be playing it, when my English comprehension was broken and the meaning of certain words escaped me, I bawled my eyes out during Snake Eater’s ending. I didn’t understand, yet, that I could throw a snake at a patrolling guard, or challenge Ocelot to a revolver duel, or set my console’s calendar forward to rob my friend, the End, of his final battle. The language barrier blurred the game’s political depth and narrative intricacies. Still, I cried because I knew Naked Snake and the Boss loved each other, and it was tragic that one of them had to die. Now one stands alone at the other’s grave and sheds a single tear.

It was painting. It was magic. It was art.

The game’s visual presentation sets the tone, even with its ending scene: a rolling fog that blankets the graves as plumes of light seep in. It is somber grey, sullen, and naturalistic. In the remake, the bright sun clears away the fog, and the headstones gleam like rows of teeth. The rays of light banish the darkness and sterilize the scene, and I remember these are blankets of code and computer-generated 3D models composed in Unreal Engine. And I forget that the one who lies in the grave was once a human.